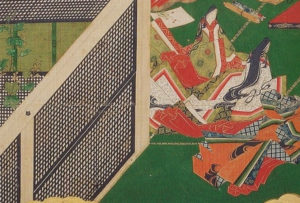

A few months ago I finished reading The Tale of Genji by Murasaki Shikubu. At over a thousand dense pages with plenty of footnotes, it was no small undertaking but absolutely worth the effort. This post will be something of a review along with my thoughts and observations. It won’t be academic but it will be quite long. The included images are all taken from this Tuttle edition of The Pillow Book by Sei Shonagon which was contemporary to the novel (and just as well known), which I hope the publisher won’t mind me reproducing here.

The Tale of Genji is arguably the greatest work of literature produced in Japanese history and certainly up there with the best humanity has produced. The author, Murasaki Shikibu was a lady-in-waiting in the Heian Court and the work was composed between 1000-1012 AD. Shikubu was also a contemporary of Sei Shonagon who wrote The Pillow Book, another beloved work of the period. The major contrast with the latter is the Shikibu’s work is fictional, though fiction drawn very much from the culture of court life in the period.

The Tale of Genji is also arguably the first novel ever written though this is something that can be quibbled about endlessly and I’m sure academics do. It is not structured in a conventional way and many scholars argue that it wasn’t actually finished. When it was written, it was not printed and sold in the codex format associated with virtually every book today. It was thought to have been written in pieces that were then handed around and read at court. The intended audience would have read different sections of the book as they were able to obtain them and most would have read the book completely out of order. It is likely that much of the book was also written out of the order it is in today. It was only later gathered together in chronological order.

The first full English translation by Arthur Waley was published between 1925 and 1933 close to a thousand years after it was written. Waley’s translation is considered a classic though it has been criticised for a number of reasons including leaving out one entire chapter of the book. It has been translated multiple times since. The most recent translation as of writing is by Dennis Washburn who also wrote the introduction to the copy I possess. I was not aware of all this when I began and the edition I read is the Waley translation and I will be drawing completely from this edition here. It is important I mention this as many character names do differ in other translations.

The book largely concerns Prince Hikaru Genji, the son of the Emperor and his consort, Kiritsubo. From his birth and early childhood, Genji is said to be strikingly handsome. “Hikaru” can be translated as “Shining One” and he is known as “The Shining Prince”. At the beginning of the book, Genji loses his mother and is removed from the line of succession though still loved and held in great esteem by his father.

The tale quickly moves from his birth and early childhood into what becomes an extended adolescence. The vast majority of the book revolves around Genji’s pursuit of love affairs. The language used by Waley, (which I assume is true of the original text), approaches this with some subtlety. This is not simply a gratuitous romance novel nor is it pornographic in the slightest. Although given its age and sex of its author, it does suggest that women have been writing on much the same subject for a long time and even in cultures that were at the time, mostly cut off from the rest of the world.

The novel is not only set in the Heian period but most of the events occur in the capital (modern Kyoto), with some much rarer ventures outside as far as Tsukushi — located in modern Fukuoka. Genji is also at one point exiled to Suma which is now part of the city of Kobe. Most of the major characters are those who move in and out of court life as their fortunes rise and fall. Those who live not just outside Japan but outside of the capital are considered unfortunate — if not barbaric. The society of court is also extraordinary effeminate considering the time period and it is little wonder this order eventually fell to a more virile one. Thankfully the successors were not so barbaric as to have destroyed all the artistic fruits of the period.

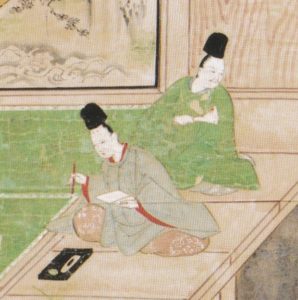

When Genji is not pursuing love affairs, there are extended and fascinating sections of the book dealing with composition poetry, the production of artwork, calligraphy, music and even a whole chapter where Genji’s household are producing perfume in competition with each other. The work is also filled with descriptions of court procedure, festivals and religious observances dotted throughout the calendar year of the time. These might not sound interesting to the average reader but it was these portions that engrossed me the most.

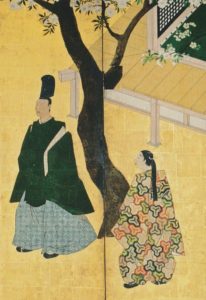

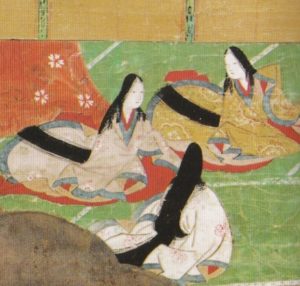

A good hand for calligraphy and an equally good mind for poetry was something of a necessity for survival at court. Women were hidden behind screens and curtains and were not often seen even when men were having an audience of with them. To put in perspective how strict this was, there is a part in the book when Genji’s son Yugiri accidentally catches a glimpse of Murasaki, Genji’s second wife whom he had never seen before despite residing in the same palace. He is overcome by her beauty and continues to watch her with full knowledge of the impropriety and scandal it could cause in the household.

The exchange of letters was then an important part of courtship and men could fall for women based on the delicacy of their hand or poetic ability alone. Conversations between characters too, often quote or paraphrase poetry. Women were not generally taught the Chinese characters, so letters to and between women were usually written using Japanese characters. The book was written this way and when Japanese students today study the text, they have some of the same difficulty English speakers have in reading Chaucer. I am not sure if this is a completely apt comparison as I’m not familiar enough with Japanese to state for sure.

Unsurprisingly voyeurism was common and almost expected though I doubt this remained so for those that were caught. Still, there are multiple scenes in the novel where Genji or another character creep to a window, curtain or door to catch a glimpse of a woman they desire. There are even moments when men force their way in to these quarters and carry off these women without any spoken consent. Living in Japan, I found the still common voyeuristic behaviour disturbing but like much else, it seems to have some historical basis. It is important to also add that seeing a woman’s sleeve was enough to send men into a frenzy so these aren’t strictly comparable to looking into female washrooms or up skirts on a busy train.

If the book is to be believed, love affairs and these intrigues were quite prevalent and non-fiction The Pillow Book by Sei Shonagon would also support this. The question of whether or not it was thought moral though is something else. I would conclude from my brief study that this is a complicated question. Monogamy still existed though those at court who could afford it, could keep concubines as well as carry on affairs elsewhere. As the birth of Genji verifies, the Emperor’s status as a living deity didn’t put him above this and being illegitimate didn’t place you outside society as it would in European courts. The Emperor had an official wife as the Empress but also what could be described as a harem within the palace. Genji had at least three women under the same roof at one stage — all of whom he was sexually intimate with.

This situation was far from harmonious though as outbursts of anger, jealousy, betrayal and unfaithfulness were common sources of conflict in the novel and art was obviously imitating life. Genji and his first wife Aoi were barely on speaking terms at most of their meetings. His second wife Murasaki was literally kidnapped as a child and brought up to become his concubine. When exiled in Suma, he has an affair with a lady living in neighbouring Akashi who gives birth to a daughter. The daughter is raised for a time by Murasaki had no children and this daughter eventually becomes Empress. One of the most dramatic subplots involves Genji’s affair with his father’s favourite concubine, Lady Fujitsubo. She gives birth to a son who goes on to become Emperor Ryozen as he was believed to be the Emperor’s son. This remains a secret to the former Emperor and the public but is known by Fujitsubo, Genji, a priest and eventually Ryozen himself.

It is an affair with a young woman in a rival family that results in Genji’s exile, and following his return he is a changed by the experience. As the prince ages, he loses a lot of the virility that got him into so much trouble as a youth but never fully. Yugiri, his son from his first wife, Aoi is far more restrained in his passions though even he has love affairs. One in particular disappointed me as it followed the marriage of his childhood sweetheart, Kumoi which had been long prevented by their families; somewhat like a Japanese Romeo and Juliet.

The Tale of Genji is largely about Genji but Genji dies about two thirds of the way through. The final third of the novel opens, “Genji was dead, and there was no one to take his place.” And indeed the focus on not one but two men for the remaining pages of the tale bares this out. Niou is the son of the Emperor and Genji’s daughter of the Lady from Akashi, making him his grandson. He is a friend and sometimes rival to Kaoru whose father is Kashiwagi, the son of Genji’s best friend To no Chujo. Kashiwagi had an affair with Genji’s third wife following Murasaki, the favourite daughter of Emperor Suzaku named Nyosan. This is known by Genji but Kaoru is assumed by most to be his son and only later discovers who his true father was. This affair also brings the narrative of Genji’s life to a neat completion with him suffering the same indignity he’d put so many through. To Genji’s credit, although learning of the affair, he never makes it public though it could be allowed that he did this also for his own reputation as well as Nyosan’s.

The narrative then is quite complicated and I found myself having to refer back to the book to remember names and who married who and who had an affair with who. It doesn’t help that the names are changed in different translations and apparently hard to identify in the original Japanese too.

The narrative with Niou and Kaoru focuses largely on Kaoru’s discovery of two young women living near a river in Uji, just outside the capital. Niou takes after Genji when it comes to women while Kaoru could be said to embody Genji’s more spiritual side that develops later in his life. Despite his pretensions to the contrary, Kaoru is in reality, no less interested in the fairer sex. The two women Agemaki and Kozeri are the daughters of Prince Hachi no Miya, the younger half-brother of Genji. Kaoru falls in love with Agemaki but this is never openly reciprocated though the text suggests she loved him. Agemaki becomes one of many characters to fall into sickness despite her young age and passes away. Niou at the same time, has little trouble seducing Agemaki and eventually sets her up as a concubine in the capital.

It is worth stopping for a moment to discuss the connection between sickness and the spiritual realm that is prevalent in the novel. Genji loses a lover named Yugao who it is said was possessed by spiritual forces and dies. Many characters fall into melancholy brought on by loss of favour with or betrayal by their lovers. Characters are regularly calling in priests to excise demons and characters who have a significant moral failing — mostly women — take on holy orders to escape their disgrace. In Waley’s translation he employs language that Catholics and High Anglicans would be familiar with though the Buddhism had a different character entirely. Most who joined religious orders did so after living a life in the secular realm and it was rare — as well as discouraged — for the young to enter. This aspect of the novel and could be lost in all the very human intrigue I’ve focused on up to this point.

Kaoru never quite gets over the death of Agemaki and takes to visiting her younger sister Kozeri and even awkwardly attempting to seduce her. This abruptly ceases when it is discovered the two sisters have an illegitimate sister named Ukifune who their late father refused to recognise. On discovering this, Kaoru begins pursuit and discovers the girl is quite similar in looks to the late Agemaki. At this time he had already married one of the Emperor’s daughters which was a great elevation for his station. Nonetheless he has become obsessed and can think of little else.

Niou discovers this girls existence and he too begins to pursue her. Kaoru moves her to the old residence in Uji and Niou eventually discovers here there and tricks the waiting women into letting him in. This begins an affair which is discovered by Kaoru and the distraught Ukifune seeks to escape this by throwing herself into the river. She survives and is helped to take up residence in a nunnery where she takes her vows. The tale is brought to a close with Kaoru discovering his lover still lived and where she was living.

The ending is certainly abrupt and in a sense unfinished but in many ways, the story had come full circle again. It is easy to imagine Kaoru and Niou continuing their pursuit, or becoming infatuated by other women and continuing much as Genji did. I have read that Lady Shikibu may never have intended to bring the story to a complete close and would have kept writing as long as she had the will to do so. Arthur Waley believed the story was complete but this doesn’t seem to be the academic consensus.

Much like with War and Peace, there was a profound sense of melancholy after finishing the book. It felt like a world that had been open to me was suddenly closed. It was almost as if in opening the book I was opening a portal in time where I could view a world now lost. This is true in a sense because the world of the Shining Prince is now lost for better or worse and this book is the most vivid way it can be brought back to life.

Something I’m surely not alone in noticing is the preoccupation with sex in Japanese literature. Everything I’ve read from Haruki Murakami, Yukio Mishima and even to a Catholic author such as Ayako Sono seem to be preoccupied with the subject. Even Italo Calvino’s imitation extract of a Japanese novel in If on a winter’s night a traveler had the same preoccupation. One can see then that in both this and The Pillow Book that this has been a favourite topic of the Japanese for a very long time. I merely make this observation and don’t intend to offer any social or psychological explanation for this.

As also mentioned, it also indicates women authors from the very best to the very worst, tend to write about the same thing. There are multiple love triangles but much like Austen, Lady Shikibu has done this in a much more sophisticated and realistic way. Lady Shikibu almost certainly never imagined her work would ever leave the capital let alone survive long enough to be appreciated throughout the world and in cultures so alien to her own.

I can’t claim to have read widely from all over the world but from my general knowledge of world literature, it would seem only Japan has produced literature on the same level as the works of Europe, North Africa and the Levant. The Tale of Genji is the ultimate testament to this.